In a previous post, I proposed that the current set of solutions for push notifications leave something to be desired. The main issue was that they were all centralized services, which is bad for fostering an open platform on the web.

Unfortunately, centralization isn’t the only problem with current push notification solutions. Message privacy, integrity, and flexibility plague current offerings, and because application developers are forced to use the services provided by the platform, there is little room for innovation.

Mozilla has been thinking about this problem, and began researching and attempting to develop a solution at the start of this year. I had the privilege of being able to work on the project as an intern, along with another intern Alexandru Amariutei, and our two mentors: Toby Elliott and Philipp von Weitershausen.

The following is my own perspective of the goals of the project, as well as its future. It does not reflect the opinion of Mozilla, though I do hope they agree with some of what I say.

Goals

Mozilla Push Notifications is a project that aims to create a system allowing notifications to be sent from providers (such as web applications or services) directly to users’ browsers. Its goals are to:

- Enable users to receive notifications on any Internet-connected device

- Make it easy for providers to send notifications to a user

- Give users full control over which providers can send them notifications

- Ensure the privacy of users is maintained throughout the use of the service

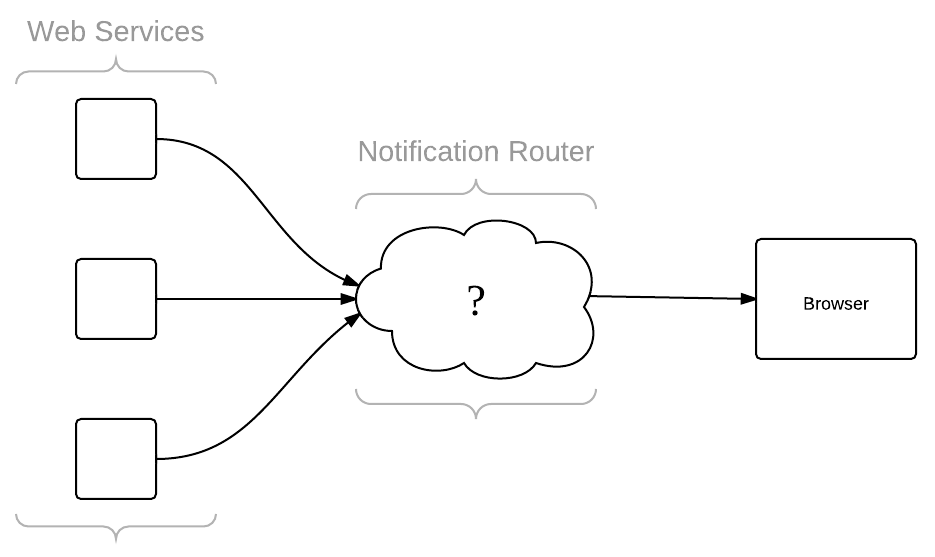

Conceptually, Mozilla is attempting to fill in the gap below:

However, what isn’t shown in the illustration above is how this service is presented to the user. This becomes a UX problem, and a difficult one at that. While indeed important, our focus was first and foremost to build a platform, and so that’s the topic of the remainder of this post.

How It Works

While I would love to go into the nitty-gritty details of how the prototype we built works, it’s already been documented to a respectable degree, and these details will almost certainly change in the final product. Instead, I’ll go over how everything is intended to work at a high level, and how this behaviour satisfies the goals the project set out to accomplish.

First of all, when a user visits a notifications-enabled web site, the page served by that site will request to send the user notifications through an exposed JavaScript API, similar to the following:

navigator.pushNotifications.requestPermission(appName, callback) {

{"app_name": "GMail",

"account": "[email protected]"},

callback,

);

function callback(token, encryptionKey, hmacKey, notifServerURL) {

...

}The browser responds to this request by presenting the user with some sort of dialog saying that the website wants to send them notifications, giving the user the option to accept or deny. If the user accepts the request, the browser executes the callback function, passing in a collection of important keys and an address. These keys are important to the system as a whole, so it’s worth discussing them in detail.

Subscription Keys

Each time a line of communication is set up between a web service and a user, we call this a subscription. It is a somewhat natural name for it, as the user is technically subscribing to receive notifications from the web service. What is different, however, is that unlike real-world subscriptions, notification subscriptions are encrypted, digitally signed, and require no personal information (e.g., your name or email) in order to work. To accomplish this, a subscription carries with it three pieces of information:

- A key used to encrypt and decrypt all information sent to the user

- A key used to sign the message to ensure its contents have not been tampered with

- A unique token used to identify this subscription, acting as an address to ensure the user’s anonymity

When a user subscribes to a web service, these three keys are randomly generated to ensure each subscription is completely private between the web service and the user. These keys are passed back to the web service via the callback function mentioned above. It’s then up to the web service to send that information securely back to a server of some kind for storage, but typically it’ll be a simple AJAX request.

Sending Notifications

With this information stored on its servers, the web service can now send push notifications to the user at any time, by sending a POST request with the notification and the given subscription token to the notification server the user’s browser specified when the subscription was initially created.

This POST request is encrypted using the key given to the web service when the subscription was created, and digitally signed with the other key to ensure its contents have not come from anyone except the service (in order to prevent replay attacks, the web service would have to include some sort of message identifier that increments with each message sent, so that replays are easily detected).

Security

When Mozilla released Firefox Sync, a significant difference between it and other sync solutions of the time was that all encryption was handled client-side. Mozilla did not want to know anything about your browsing history, tabs, or passwords—your personal data was only viewable by you.

The problem with Apple’s and Android’s push notification solutions is that there is no notion of privacy other than “trust us.” This isn’t to say that either Apple or Google are evil companies—the problem is merely that they have access to all messages that have been sent to you. If any of these services were to be compromised—or even more likely, subpoenaed—you personal messages can be read by someone with whom you have not placed your “trust”.

Keeping this in mind, Mozilla designed the push notification server to encrypt all messages from the point they leave a web service to when they are finally received by a user. This ensures privacy that other push notification frameworks ignore.

Looking Ahead

With a working prototype implemented, my work as an intern was done, but the project has really only just begun. After demonstrating our prototype to the company, Mozilla has decided to go ahead and invest more resources into the project to make it a reality.

In order to encourage adoption, Mozilla will eventually build notifications support into its Firefox browser, giving its large user base the ability to receive notifications, and hopefully encouraging web services to start adding support for notifications using Mozilla’s platform. The aim here isn’t to get everyone to use Mozilla’s servers for getting their notifications, but rather to expose more users to the concept of notifications, with the hope that this will coerce other browsers into adopting the standard and adding support to their own browsers.

Reflection

Working on this project was certainly eye-opening, as the types of issues we had to think about while designing and implementing the prototype were fundamentally different than any I had ever experienced at another company. It’s one thing to design something to scale and be secure; it’s a completely different scenario when you set out to design something for the betterment of the web.

In the end, I walked away from the experience with a greater appreciation for Mozilla, and I must say I admire the spirit of this company and the people who work to uphold its mission. I look forward to seeing how far this project—and this company—will go.